In today’s society, we are constantly fed with hundreds of images everyday. As a result, we often accept the images without questioning the meaning behind them, and also because photographs have historically captured truth. If used positively, images serve a positive function, as tools that effectively convey messages universally, without the hindrance posed by the language barrier. Nevertheless, we are often subjected to propaganda images that have been misused through their removal from their proper context. Often as a society we overlook how these images are being framed in newspapers or on posters, and accept them as the truth without questioning the true intent of the presentation. In actuality, most of the time, images in the media are posed by photographers and Photoshopped by editors, and most of the time, we are unaware of these changes and the meaning contained within these photographs.

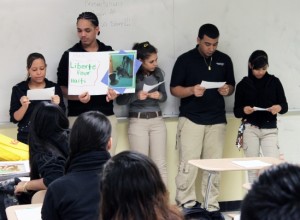

It is important to know the way each photograph is being used. An interesting art project posted on Urban Arts Partnership, incorporated into two global history classes taught by teaching artist Elise Rasmussen and Ms Delgado, helps students understand the usage of media photographs more fully. Throughout the year, students are incorporating photography and the visual arts to illustrate historical concepts and eras from the curriculum. One global history class, which explores student political revolutions around the world, utilizes photography to understand the roots of revolution and how it affects people. The students work together in groups to create propaganda posters that relate to specific revolutions. They present these to the class and explain their usage and background to their fellow students. Studying historical propaganda photographs and remaking them allows students to grasp the concept that not all photographs represent the truth. They created photographs to create the posters that helped to fuel their revolutions. This can also be done by governments and radical groups. This interactive technique in approaching the study of history allows students to grasp better the relationship between photography and propaganda. Even photography classes rarely address the fact that many photographs do not only convey the truth and are used in the wrong way. We should question the validity of images and their intention.

The main emphasis of this project is on illustrating historical events through interactive group artwork, which provides a new and exciting way for students to learn and reflect upon history. However, through the recreation of propaganda, the project also helps students to be more aware of their own media and the present time. This teaching method can be applied in most classes, to help students to gain a better understanding of their own culture and remind them not to believe every image they see. It would form a crucial part of cultural studies in the current era, especially in view of the growth rate of Photoshopped images and the fact that many young teens still believe in the truth of all the images that they see online and in magazines. There are also movements like SPARK, which has demanded that Teen Vogue show real, untouched photographs of girls. However, such single-issue activism is not enough. The misuse of images goes far beyond fashion magazines—it extends to human rights issues in the news. It is vital to educate young adults about the massive increase in photographic manipulation and synthesis.